A sabbatical in Africa – a year in Malindi

I have been here for two months now. Here being Malindi, on the east coast of Kenya in East Africa. Having completed the preparatory chores for my sabbatical (such as establishing basic communication lines, finding accommodation, buying an old four-wheel-drive) I am now settling down to what I hope will be a calmer and more inspirational part of my ‘year out’ in the quiet existence of this small, ancient trading port with its strong Arab and Portuguese imprints. No access to TV, radio or newspapers means I feel deliciously cut off and strangely ‘protected’. I guess if there is something I need to know, people will let me know soon enough.

I have been here for two months now. Here being Malindi, on the east coast of Kenya in East Africa. Having completed the preparatory chores for my sabbatical (such as establishing basic communication lines, finding accommodation, buying an old four-wheel-drive) I am now settling down to what I hope will be a calmer and more inspirational part of my ‘year out’ in the quiet existence of this small, ancient trading port with its strong Arab and Portuguese imprints. No access to TV, radio or newspapers means I feel deliciously cut off and strangely ‘protected’. I guess if there is something I need to know, people will let me know soon enough.

Meanwhile, and despite living in a Muslim community, I am blissfully unaware of what is happening in the world of angry men (Bush, Sadam, Blair, Bin Laden – who are they?) and devote myself to the serenity of more important matters – like simple living and feeding my soul. And painting.

Meanwhile, and despite living in a Muslim community, I am blissfully unaware of what is happening in the world of angry men (Bush, Sadam, Blair, Bin Laden – who are they?) and devote myself to the serenity of more important matters – like simple living and feeding my soul. And painting.

I am reluctant to mingle much despite frequent invitations from mostly retired locals whose boredom spurs them to entertain – if only to see a new face now and then. However, I do try and brush up my Swahili by chatting to my African neighbours – the cooks, fishermen and shopkeepers. All Kenyans are now so well educated compared to when I lived here 25 years ago. They tell me proudly that Kenya has the highest literacy rate in Africa due to its free education policy. All a parent has to do is supply a school uniform, which of course takes quite a bit of saving – unless their European employers provide them for free.

Increased knowledge has graced them with more confidence – they seem more relaxed and more at ease and show an insatiable appetite for general knowledge no matter the subject. On the whole (at least here at the coast where food is plentiful and plenty of employment with tourism) people seem to make enough money to live comfortably. A general feeling of ease and contentment pervades and, when things do occasionally go wrong or irritate, most Africans merely display an acceptance and patience that is equalled only by the wise men from the East…

I have spent these last two months care-taking a house of a friend’s mother who has been holidaying in Europe. The house is large with spacious verandas on both floors. From there I have a birds’ eye view of 2 acres of spectacular gardens that horticulturalist Joan, aged 84, still takes care of herself, albeit now with the help of two gardeners. There is an astonishing array of indigenous plant species, many of them rare and each smelling differently from the next. Bright shiny leaves oozing with the juices of life, dark dry mystical specimens, frivolous attention-seekers and soft, voluptuously furry numbers. Some flowers are more delicate than the daintiest dandelion seeds, others somewhat crude with long phallic or weird bulbous shapes – all are set amidst splashes of the most deliciously clashing colours of bright pinks, purples, oranges, yellows and reds…

I have spent these last two months care-taking a house of a friend’s mother who has been holidaying in Europe. The house is large with spacious verandas on both floors. From there I have a birds’ eye view of 2 acres of spectacular gardens that horticulturalist Joan, aged 84, still takes care of herself, albeit now with the help of two gardeners. There is an astonishing array of indigenous plant species, many of them rare and each smelling differently from the next. Bright shiny leaves oozing with the juices of life, dark dry mystical specimens, frivolous attention-seekers and soft, voluptuously furry numbers. Some flowers are more delicate than the daintiest dandelion seeds, others somewhat crude with long phallic or weird bulbous shapes – all are set amidst splashes of the most deliciously clashing colours of bright pinks, purples, oranges, yellows and reds…

Here and there, tucked away, the gardens also hide shaded plots for vegetables and herbs, a potting shed and secret paths as well as a large swimming pool. From upstairs I am at eye level with the many bird species that flutter around the tree branches but in the undergrowth lives another world of creatures, scuffling about doing their daily business – hedgehogs and lizards and newts and frogs and dormice with soft fluffy tails, colourful beetles and many species of ants and praying mantises. It is a cruel world among those insects where the winner always wins and the looser always loses. And yet it all seems like paradise from up here…

Here and there, tucked away, the gardens also hide shaded plots for vegetables and herbs, a potting shed and secret paths as well as a large swimming pool. From upstairs I am at eye level with the many bird species that flutter around the tree branches but in the undergrowth lives another world of creatures, scuffling about doing their daily business – hedgehogs and lizards and newts and frogs and dormice with soft fluffy tails, colourful beetles and many species of ants and praying mantises. It is a cruel world among those insects where the winner always wins and the looser always loses. And yet it all seems like paradise from up here…

Literally two minutes walk from this heaven-on-earth is a deserted and sparkling white sandy beach, scattered with palm trees and edged by tall NEEM – the ‘magic’ trees which are said to be capable of curing or warding off 60 diseases. At high tide, there are deep rock pools in the warm Indian ocean, making it a safe and comfortable place for swimming and snorkeling. And on the beach the traditional fishermen chat while repairing their nets and sails, or they rest beside their hollowed-out tree-trunk NGALO‘s in which they go fishing at night. They sometimes take me out to the reef where they fish for lobster and crab. Occasionally a romantic ancient Arab dhow glides by – those elegant, century-old, hand-carved wooden ships with hand-sewn, patched-up Egyptian cotton sails.

Literally two minutes walk from this heaven-on-earth is a deserted and sparkling white sandy beach, scattered with palm trees and edged by tall NEEM – the ‘magic’ trees which are said to be capable of curing or warding off 60 diseases. At high tide, there are deep rock pools in the warm Indian ocean, making it a safe and comfortable place for swimming and snorkeling. And on the beach the traditional fishermen chat while repairing their nets and sails, or they rest beside their hollowed-out tree-trunk NGALO‘s in which they go fishing at night. They sometimes take me out to the reef where they fish for lobster and crab. Occasionally a romantic ancient Arab dhow glides by – those elegant, century-old, hand-carved wooden ships with hand-sewn, patched-up Egyptian cotton sails.

At this stage I have moved into my little rented tree house – a rather primitive structure built around a tree, but it does have electricity (between daily powercuts). The house also has a rudimentary bathroom (hot water comes with the help of a solar panel) and a tiny but well-equipped kitchen with a basic stove and a large fridge which doubles as cupboard to protect dried foods from its many potential predators. There is chicken wire but no glass in the little windows and there are no curtains..

At this stage I have moved into my little rented tree house – a rather primitive structure built around a tree, but it does have electricity (between daily powercuts). The house also has a rudimentary bathroom (hot water comes with the help of a solar panel) and a tiny but well-equipped kitchen with a basic stove and a large fridge which doubles as cupboard to protect dried foods from its many potential predators. There is chicken wire but no glass in the little windows and there are no curtains..

Every room contains treasured possessions – not valuable in money-terms, but  beautiful and cherished snapshot memories from a bygone era, inviting one to dream and fantasize. Though often chipped or cracked, I never tire of reveling at the old crockery and photos, of touching the old books and art on the walls, of stroking the worn furniture and fabrics faded by the harsh African sun. It’s a delightful mishmash – a secret glimpse into another world.

beautiful and cherished snapshot memories from a bygone era, inviting one to dream and fantasize. Though often chipped or cracked, I never tire of reveling at the old crockery and photos, of touching the old books and art on the walls, of stroking the worn furniture and fabrics faded by the harsh African sun. It’s a delightful mishmash – a secret glimpse into another world.

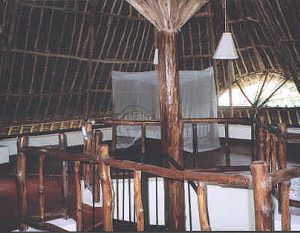

Like most of the houses here, my treehouse is built entirely from local materials, with walls of hand-cut old coral ‘bricks’ framed by mangrove, mango or sisal poles – then white-washed with lime.

Roofs are made of makuti (palm-leaves) and inside some ceilings are lined with hessian to prevent snakes from accidentally dropping down. At the top of the house, in among the tree branches, my favourite room with a wooden floor, sensually mellowed with years of wax polishing, and evocative Arabic hand-carved furniture with cushions in colourful local fabrics. This room also has a palm-leaf roof but it is open at the sides, making it a cool and breezy place to sleep on a hot night. Needless to say, the sound of the pounding surf of the Indian Ocean is ever-present.

The garden here is not manicured like Joan’s but a maze of little jungle-like paths interspersed with shabby-chic seating areas, salvaged birdbaths and follies made out of found objects – plenty of places for quiet contemplation or a cooling drink in the dapple-shade of the tall NEEM trees. My treehouse is the only property of some 20 I have viewed that is not surrounded by railings, fences or gates. I have little of value so why would I want to imprison myself? Especially when this allows the fisherman to come to the house to sell me just-caught clams, crabs and lobsters! There are two patios, one east and one west of the house so there is always shade to be found on one, and this is where I have breakfast, lunch or dinner, paint or ponder under the stars. Both patios have rustic furniture made from driftwood that are scattered with more cushions covered in brightly patterned locally dyed fabrics.

The garden here is not manicured like Joan’s but a maze of little jungle-like paths interspersed with shabby-chic seating areas, salvaged birdbaths and follies made out of found objects – plenty of places for quiet contemplation or a cooling drink in the dapple-shade of the tall NEEM trees. My treehouse is the only property of some 20 I have viewed that is not surrounded by railings, fences or gates. I have little of value so why would I want to imprison myself? Especially when this allows the fisherman to come to the house to sell me just-caught clams, crabs and lobsters! There are two patios, one east and one west of the house so there is always shade to be found on one, and this is where I have breakfast, lunch or dinner, paint or ponder under the stars. Both patios have rustic furniture made from driftwood that are scattered with more cushions covered in brightly patterned locally dyed fabrics.

The house comes with a loyal old servant called Baya who wears sophisticated horn-rimmed glasses that make him look like an old, learned professor. He is a quiet, sensitive man who takes care of me like I am his daughter. His passion is polishing the owner’s copper and brass objects and when I paint under the NEEM trees, he likes to position himself beside me for hours – occasionally glancing over my work and nodding in quiet approval or shaking his head and chuckling at my insanity of painting still lives of fruit and vegetables. I like his content companionship. Our gurus tell us to concentrate on the present, to live in the now and to take pride in every little chore. We work hard to achieve this state of peace but to the African most of this comes naturally. Everything Baya does gets his full attention and infinite care – not only without complaining but with total dedication and pride. I have learned much from him. The idea of ‘employing a servant’ may repulse some of us, but it is worth acknowledging that most Africans consider that giving employment is possibly white-man’s only useful purpose in Africa today..

The house comes with a loyal old servant called Baya who wears sophisticated horn-rimmed glasses that make him look like an old, learned professor. He is a quiet, sensitive man who takes care of me like I am his daughter. His passion is polishing the owner’s copper and brass objects and when I paint under the NEEM trees, he likes to position himself beside me for hours – occasionally glancing over my work and nodding in quiet approval or shaking his head and chuckling at my insanity of painting still lives of fruit and vegetables. I like his content companionship. Our gurus tell us to concentrate on the present, to live in the now and to take pride in every little chore. We work hard to achieve this state of peace but to the African most of this comes naturally. Everything Baya does gets his full attention and infinite care – not only without complaining but with total dedication and pride. I have learned much from him. The idea of ‘employing a servant’ may repulse some of us, but it is worth acknowledging that most Africans consider that giving employment is possibly white-man’s only useful purpose in Africa today..

Whilst there are no luxuries in my little house (if you don’t call having your clothes laundered and ironed a luxury) it is a very magical place. The chicken wire in the windows is there to stop the monkeys or monitor lizards from entering. There are no smart, shiny surfaces or gleaming taps. My toast is made on an old wire rack over an open flame, my wardrobe is a horizontal sisal pole hidden behind a cotton curtain, my shower water is heated by the sun and my lighting comes mostly from paraffin. But there is nothing lacking. Semi-transparent mosquito nets romantically waft in the breeze, blooming gardenias perfume the air around me, twittering birds provide the background music and there is total and utter peace. Things cannot get more idyllic.

And yes, the milk goes off if you leave it out for 10 minutes, and the roads are full of potholes (sometimes the size of one’s car), you can never count on electricity, the network in the internet cafés is mostly down and the shops run out of things. But you can get live prawns the size of a baby’s arm an hour after they were caught, a bucket of crabs or clams costs a few pennies, and the most famous HALWA in the world, made with fragrant pistachios and cardamom, is made right here in Malindi and exported all over the world. And there are sunsets to make you cry with the beauty of it all. Life is good here. If it weren’t for that giant Colobus monkey that keeps me awake at night by ripping at my delicately knotted makuti roof. But sweet old Baya has promised to catapult it away tonight. No doubt the darling man will insist on giving up his night’s sleep to squat in front of his little house, ready to pounce when the baboon appears. Whatever it takes to please or protect me. No use me saying otherwise. He considers it his job. And his pleasure.

And yes, the milk goes off if you leave it out for 10 minutes, and the roads are full of potholes (sometimes the size of one’s car), you can never count on electricity, the network in the internet cafés is mostly down and the shops run out of things. But you can get live prawns the size of a baby’s arm an hour after they were caught, a bucket of crabs or clams costs a few pennies, and the most famous HALWA in the world, made with fragrant pistachios and cardamom, is made right here in Malindi and exported all over the world. And there are sunsets to make you cry with the beauty of it all. Life is good here. If it weren’t for that giant Colobus monkey that keeps me awake at night by ripping at my delicately knotted makuti roof. But sweet old Baya has promised to catapult it away tonight. No doubt the darling man will insist on giving up his night’s sleep to squat in front of his little house, ready to pounce when the baboon appears. Whatever it takes to please or protect me. No use me saying otherwise. He considers it his job. And his pleasure.

My senses too are acutely alive here – almost exaggerated. I can smell approaching rain an hour before it arrives. And I can smell when the tide is in or out without looking at the sea. Everything has a smell and they all become familiar – like the scent of corn being roasted over charcoal at the roadside stalls, or the sweet smells of wild frangipani flowers or fragrant ripe mangos; the acrid whiffs of melting rubber or a roaming goat, the pungency of melting rubber, of rancid butter or worn leather and even the stink of rotting vegetables – are all the smells that make up Africa.

And then there are the sounds of a million different birds – whooping, cawing, singing, fluttering, the buzzing of an insect, the cackle of hens that run around freely everywhere, the excited chatter of Muslim women dressed in their black nuiqab‘s, children laughing and playing in the cool of the evening with toys made of old empty food cans, and running up a palm tree for the precious milk in a green coconut becomes a game. The spiritually soothing, monotonous Muslim prayers that are blasted across the town from garishly decorated mosques at 6am.. The old men in squeaky clean white habits and prayer-hats on their way to evening prayer. And their gentle greetings – the way they lightly touch their foreheads and hearts. Hujambo Mzee. Salaam aleikum. Aleikum salaam.

Everything becomes a precious experience. The mousquito-chasing swallows that swoop an inch over my head while I have my evening swim in the twillight.. The hedgehog trundling through the garden as I walk back to the house.. And as I’m sitting here typing on the veranda, there is a flowering orange-red ‘flaming’ Thika tree beside me that is alive with dozens of chattering sun birds in all the stunning colours of the rainbow. And right now, among the racket of nocturnal frogs and crickets, I can hear a little bush baby calling.

Feeding my soul alright. By the bucket-load. To overflowing.

By Petra Carter,

Malindi 2003